I knew Lavern for many years prior to his death in 1995. He was the nicest, most soft-spoken gentleman you would ever have the pleasure of meeting. Despite his fame, he was always humble about his abilities and was always willing to take the time to talk with people about his artwork. We used to have him appear at The Farmers' Museum's annual Harvest Festival to demonstrate his carving, and our visitors - particularly the children - were just entranced by the casual manner in which he sculpted basswood while carrying on a conversation.

He could also write. We have in our files several lengthy and remarkably well-written letters describing his work and his approach to particular pieces. They are worth sharing.

In 1988, the Fenimore Art Museum commissioned two pieces from Kelley. We did not specify what they were to be, only that we wanted two people about three feet tall each. The rest was up to him. Here is how he described his thought process:

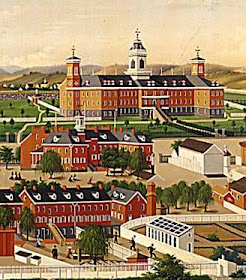

When I was first approached concerning the commissioned two figures for the Fenimore Art Museum, I felt both elation and surprise. I had never had a commission of this size before. Since The Farmers' Museum, located across the road, and also a part of the museum campus with the Fenimore, keeps mainly to before the turn of the century in their displays, I thought it would be fitting to make the new pieces from that period.

Usually, a blacksmith was one of the most important people in town, so I settled on a blacksmith for the male figure. I felt this was fitting, too, because there is an active blacksmith shop at The Farmers' Museum. The female figure, however, posed a little bigger problem, since women were not as highly visible in that period. The two most obvious walks of life for a woman at that time would have been the housewife or the schoolmarm, at least that was all I could think of. I settled on the schoolmarm, and this also fitted in nicely, because there is a schoolhouse across the road at the museum.

Lavern worked on the blacksmith for about five months, in between his seasonal farm chores. The schoolmarm, completed in the winter, went faster. The finished pair have graced our galleries off and on for many years now, and every time I see them I think of the two museums on our campus - the Fenimore Art Museum and The Farmers' Museum - and the cultural ties between them that too few people grasp. I also think of the unassuming local farmer who saw it all so clearly and expressed it so beautifully in wood.