My annual family trip to Martha’s Vineyard is a great time to reconnect with the great seafaring traditions that are far less evident in landlocked Cooperstown, New York. The Vineyard was a major whaling center in the early decades of the nineteenth century, when whale oil was a precious commodity and captains could get very wealthy from a single successful voyage. The best whaling was in the Pacific Ocean, so these voyages were quite long and arduous; there was no Panama Canal, so the ships had to go around Cape Horn at the southern tip of South America to reach the prime whaling waters.

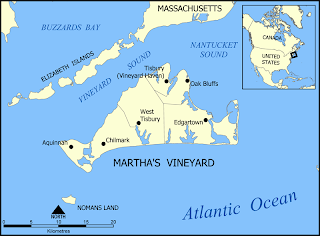

Edgartown, on the eastern end of the Vineyard, was the island’s prime whaling port, and thus it is the place where the history of whaling is most in evidence. And nowhere is it more prevalent than the Westside Cemetery right in the heart of town, where many of the ship captains are buried and commemorated in stone.

These gravestones hold a particular fascination for me, of course, as exceptional examples of American folk art. They were created by craft-trained stone carvers who over time developed their own distinctive styles. A comparison of two weeping willow vignettes on two Edgartown gravestones illustrates this point. One of the trees is quite realistic in its rendition, while the other is very stylized and nearly abstract.

Of all the gravestones in Edgartown, there is one that I have to pay my respects to every time I come here. From a distance you would hardly notice it. It carries no elaborate decoration and is a fairly standard shape. As you get closer you realize that there is a lot of writing, but it is only when you begin to read that you become riveted to the spot. Here is how it starts:

“Capt. Archibald Mellen, Jr., born at Tisbury June 5, 1830, and murdered on board ship Junior of New Bedford off the coast of New Zealand Dec 25, 1857: by Cyrus W. Plummer.”

Wow. Sure beats the sappy romantic pieties of the usual gravestone inscription. Think about it: not only does his tombstone give the gory details of the captain’s demise, it also names his murderer! An indictment in stone.

The story of the murder is well known, and one of the more famous mutinies involving Vineyarders. According to the histories of the voyage, Captain Mellen was on a whaling voyage near New Zealand when, on Christmas Eve 1857, he gave his men each a cup of grog and retired for the evening. Plummer and several conspirators later stormed the cabin and killed Mellen and his third mate while wounding several other officers. The murderers threw the dead officers overboard. (I suppose this is why Mellen’s gravestone doesn’t begin with “Here lies....”)

They were later captured in Sydney, Australia, and put on trial back in the United States. They were defended by Benjamin Butler, the Civil War general, who claimed the actions were the result of ill treatment of the sailors on the part of Captain Mellen. Butler successfully reduced Plummer’s charge from mutiny to “deliberate murder.” Plummer was sentenced to hang, but his sentence was commuted to life in prison by the President, James Buchanan. And there Plummer died, years later. (The other conspirators served out jail terms and were eventually released).

Back in Edgartown, the Mellen family had none of it. They must have commissioned the stone, and used their money (and the carver’s talents) to condemn Plummer for eternity. The gravestone inscription concludes: “Thus, at an early age, at the flood tide of successful manhood, an intelligent, honest, and worthy man became the innocent victim of the insatiable ambition of these conspirators.” Case closed.